Ancient New York ocean discovery could hold secret of hydrogen storage.

Miniscule pockets of water from the ocean that covered New York state 390 million years ago have been discovered hidden inside rocks.

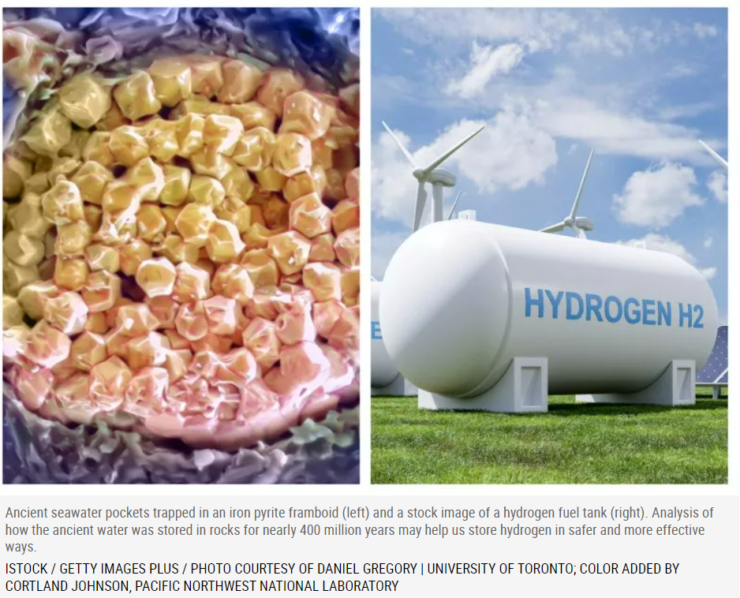

Researchers published findings in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters on November 17 that showed ancient water trapped inside an iron pyrite framboid, so-called for its resemblance to raspberries.

They were able to analyze what was inside the liquid pocket, allowing them to confirm that the water’s salt content matched the composition of the ancient ocean.

🔥 What about we co-host a webinar? Let's educate, captivate, and convert the hydrogen economy!

Hydrogen Central is the global go-to online magazine for the hydrogen economy, we can help you host impactful webinars that become a global reference on your topic and are an evergreen source of leads. Click here to request more details

One far-reaching impact of this study could be gaining further knowledge on how to safely store hydrogen fuel or other explosive gasses underground or in rocks. Hydrogen can be stored as a compressed gas, but it is highly explosive. It can also be stored as a liquid, but due to its low boiling point, this requires incredibly low storage temperatures of −252.882 °C or −423.188 °F

Sandra Taylor, the lead author of the study and a scientist at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, told Newsweek, said:

This work shows the existence of tiny defects in minerals at the nanometer scale.

“We see that they can trap water and in turn it’s likely that they could trap hydrogen as well. So with all the effort going into understanding the storage of hydrogen underground, it is important to consider what role these defects may have and we think we can apply this approach to do that.”

More effective hydrogen storage may then make a future using the cleaner fuel easier, including in hydrogen fuel cells and in nuclear fusion energy.

The researchers may also be able to use the ancient ocean pockets to find out more about the climate of the ancient Earth, and how it changed over time.

Daniel Gregory, a geologist at the University of Toronto and co-author of the study, told Newsweek:

We made this discovery analyzing the mineral pyrite, trying to understand whether pyrite’s trace element content can affect how fast it oxidizes, but we were using a very high resolution technique, atom probe tomography (gives nanometer scale 3-D reconstructions of the sample) and when we processed the data we found that things were more complicated than we’d anticipated.

“We were using natural pyrite samples that formed in the oceans hundreds of millions of years ago and what we found in the APT data was that extremely small droplets of water were preserved in the pyrite sample, possibly from the oceans from which the pyrite formed.”

“To follow up on this we checked the Ca [calcium], Mg [magnesium], Na [sodium], and K [potassium] concentration to see if it matches sea water concentrations. While Na and K seemed to be a little different than expected Mg and Ca were very close,” Gregory said.

This is important because Ca and Mg are used to determine, among other things, past ocean temperature.

“Thus, we may have found a new tool to understand Mg/Ca ratios through geologic time. This is important because current methods use evaporite deposits which are relatively rare in the geologic record whereas pyrite is very common in the geologic record so it may lead to a greater understanding of the evolution of the oceans and climate through time,” Gregory said.

By garnering information about the conditions on ancient Earth, researchers can better understand how changing climates affect life; water mineral content gives clues about ocean temperatures, among other factors.

About 390 million years ago, when the water is thought to have become trapped inside the rock, was during the Devonian period, which spanned 60.3 million years. However, it is rare to encounter liquid water from millions of years ago, making it hard to get a true picture of the environment.

Timothy Lyons, a biogeochemistry professor at the University of California, Riverside, and co-author of the paper, told Newsweek, said:

Typically we can only infer past ocean chemistry through indirect chemical means because that water is no longer preserved in the samples.

“These new findings provide a surprising and potentially very powerful way to trace evolving ocean chemistry, and the changes in the atmosphere and life by inference, far more directly through what seem to be trapped tiny pockets of seawater. If we are correct in our initial interpretations, this method could be extended up and down the geologic time scale to find many long-elusive answers about our past—and possibly our future.”

Ancient New York Ocean Discovery Could Hold Secret of Hydrogen Storage, November 23, 2022