The best way to introduce hydrogen to the market – Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro.

During a particularly hectic period full of hydrogen-related activities, I found a little time to break my writing hiatus with another opinion piece; this time I want to talk about what I think the best way is to introduce hydrogen to the market.

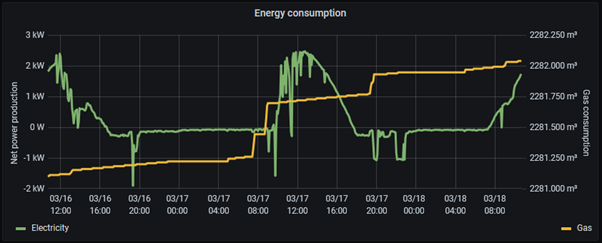

One of my hobbies is related to the Internet of Things, mainly about tinkering with sensors at home to see if I can make my life easier. Recently I discovered a relatively easy method (well, easy if you are an IoT hobbyist such as myself) to extract the electricity and gas consumption data from the Smart Meter I have in my house in the Netherlands. The method involves a microcontroller, a few cables, and some code from GitHub, a pretty standard IoT bill of materials. After soldering and debugging, I was happy to be able to monitor my electric consumption and my gas consumption, because this opens up a world of possibilities on how to reduce my environmental footprint. Here is a snapshot of the data I generated the past two days:

Since I have PV panels at home and the past few days have been particularly sunny, I am producing significantly more power than I am consuming (hence during the day all the net power production is positive). Interesting for me was also to notice that my hot water pipes may not be very well insulated, considering that there is a continuous creep up of the gas consumption over time outside of the times when we shower (which are pretty obvious when you look at the data). This information got me thinking again about how my energy bills (in particular about gas) are calculated and whether or not it could make sense to find a greener alternative.

🔥 What about we co-host a webinar? Let's educate, captivate, and convert the hydrogen economy!

Hydrogen Central is the global go-to online magazine for the hydrogen economy, we can help you host impactful webinars that become a global reference on your topic and are an evergreen source of leads. Click here to request more details

Some time ago I wrote an article about hydrogen for homes and whether or not it makes sense to use it as an opportunity to scale-up the consumption of hydrogen. Back then my article was received with a bit of controversy, mainly from the defenders of the ‘system value of hydrogen’ i.e., the proponents of the idea that hydrogen should enter the markets where it is needed the most or where it can bring the most value to our energy system. I think that this is a highly idealistic scenario and that it does not reflect the actual way new technologies have been adopted by the market. The most recent example I can think of are lithium batteries.

With the recent prices for natural gas in 2021 and 2022, hydrogen could already be a cost-effective alternative that emulates the past successes on the introduction of new technologies to the market.

Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro

Let us remember how lithium batteries were introduced to the market. Back in the early to mid-2000’s no one was asking for the “system value of lithium batteries” nor did the consultancy firm Liebreich Associates (not to throw them under the bus; I have the utmost respect for their work) publish anything called “Lithium Batteries: The Ladder” (at least not to my knowledge). For decades, the main electrochemical energy storage devices used were alkaline batteries, which have the disadvantage of being single use. Afterwards came the rechargeable batteries made of nickel (either as NiCd or NiMH batteries), with the main advantage of being rechargeable but with the limitations that they have a somewhat rapid degradation rate and that their energy storage density was not very high, meaning that power-hungry electronics (such as computers) were not able to be made portable without making significant performance compromises.

When lithium batteries came to the market, with their advantages of having a higher energy density and a lower degradation rate, the market was quick to adopt them to substitute nickel batteries. First, the small portable electronics switched to lithium, and then the larger portable electronics followed suit. Why would portable electronics be interested in lithium batteries when they already had a functioning product? My take here is that it has to do with willingness to pay: the consumers of portable electronics were willing to pay a significant portion of their income to get the latest electronic device. Laptops were very expensive back in the day and so were powertools (at least the good powertools were).

End consumers (i.e., people) do not care as much about maximizing their profit or the return on their purchase nearly as much as companies do, meaning that end consumers are willing to absorb higher cost increases than companies, not to mention that individuals have a much lower lobby power than companies and company associations. Lithium batteries provided a clear advantage over the state-of-the-art technology, so it was the portable electronics market that paved the way towards lithium eventually entering the large-scale storage and vehicle markets, despite the vehicle market being a clearer application where lithium batteries would have brought a higher ‘system value’ from the very beginning.

For hydrogen it should be the same as for lithium batteries: let us find a market with a high willingness to pay and start from there. I can think of two examples: hydrogen in homes and hydrogen in cars. People consume large amounts of gas in their houses (maybe not me after I make the most out of my new energy consumption monitoring device) and are willing to buy 60k€ sedans and pay €2 per liter of gasoline or diesel. The alternative to lithium batteries in vehicles is not that much enticing either: right now, next-gen BEVs are starting at 50k€ and will have 60+kWh battery storage.

For example, the Kia Niro BEV used to come with a 35kWh and a 64kWh versions but the recently announced 2022 model will only come with the 64kWh battery. Since I was briefly interested in buying a Kia Niro, I did a research on the availability of ‘fast chargers’ (i.e., chargers with a charging rate of >100kW) around me and was a bit disappointed. Out of the 81.000 charging poles in the Netherlands, around 3.000 are fast chargers. Europe-wide, the rate of fast chargers to regular (i.e., <50kW) chargers is 1 in 10. To put the different chargers in perspective: charging 70% of a 64 kWh battery (as per Kia’s specifications) would take 7 hours at home or at a 11 kW charging pole, and ~43 minutes using a supercharger. This means that I would mainly have to depend on charging at home because otherwise I need to stay at least 43 minutes at a charging pole or wait for another BEV owner to use their 43 minutes to charge their car. In any case this is not really convenient, especially when considering the level of convenience that gasoline and diesel have made us accustomed to. For hydrogen the situation is completely different: there are only two modes of filling namely, slow filling and fast filling. What this means for cars (that will typically have a 5 kg hydrogen tank) is that they either have to wait 3 minutes at a fast fill station, or 6 minutes at a slow fill station. It’s that simple.

Now on to the subject of cost. Normally speaking, goods are sold to consumers with a price tag and a value-added tax, but this does not necessarily apply to energy carriers. Some of the most common energy carriers such as gasoline, diesel, natural gas, and electricity, are sold (depending on the country) with a high tax rate and other kinds of taxes and levies for environmental protection, security of supply, gas network operation and maintenance, etc. With (green) hydrogen, environmental protection is no longer a concern, so we could assume that green hydrogen can be sold like any other good i.e., with a price tag and a value-added tax while compounding all other levies in the price tag before VAT. With this assumption in mind, we can use the current (2022) natural gas prices to calculate how high the hydrogen price should be to be cost-competitive with natural gas in homes:

| 2021 | 2022 | |

| Fuel cost | € 0.25487 | € 0.70130 |

| Energy tax | € 0.42176 | € 0.42176 |

| Climate tax | € 0.10297 | € 0.10297 |

| Pro-rated gas supply cost | € 0.24935 | € 0.24935 |

| Total [€/m3] | € 1.02895 | € 1.47538 |

| HHV NG [kWh/m3] | 9 | 9 |

| HHV H2 [kWh/kg] | 40 | 40 |

| Equivalence NG-H2 | 4.44 | 4.44 |

| Total price [€/kg H2-eq] | € 4.57309 | € 6.55723 |

| BTW in NL | 21% | 21% |

| Equivalent H2 price [€/kg] | € 3.78 | € 5.42 |

My first reaction was: natural gas is expensive! In 2021 (before the winter, in any case) we were paying €1 euro per m3 of natural gas, and in 2022 due to many factors the prices have sky-rocketed to a total of almost €1.50 per m3. If we assume that hydrogen is taxed at 21% as most ‘luxury’ goods (even though one could argue that energy is a first-necessity good so it should be taxed at 9% just like the other first-necessity goods such as water and agricultural products), I calculated that for hydrogen to be cost-competitive with natural gas at homes it should cost a maximum of €5.42 per kg excl. VAT (€6.56 incl. VAT). Even if we take the 2021 prices i.e., €3.78 excl. VAT (€4.57 incl. VAT) and compare them with a recent estimate made by TNO and shown to the Dutch government i.e., that the domestically-produced green hydrogen in the Netherlands could cost between €3.60 and €6,50 per kg, this is an amazing result: green domestically-produced hydrogen for use in homes is right now perfectly cost-competitive with the current alternative. And this is not considering potential subsidies that the Dutch government could (and should) issue for green hydrogen to accelerate its uptake. All in all, hydrogen for homes is a great idea so it should be central to the discussions about how we can accelerate hydrogen uptake and thereby stimulate the creation of a hydrogen economy.

READ the latest news shaping the hydrogen market at Hydrogen Central

About the author

Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro is a Hydrogen Project Coordinator at New Energy Coalition. He has worked in the hydrogen industry for nearly a decade, on topics such as hydrogen electrolysis, compression, and transportation. Besides hydrogen, he is passionate about Renewable Energy Systems and the Internet of Things.

Copyright © Hydrogen Central. All Rights Reserved.