What is a hydrogen valley? – Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro.

A few weeks back I received an invitation from the municipality where I live to participate in a survey about renewable energy. The municipality wanted to know the current level of support of the residents towards the municipal plans of installing and owning a couple wind turbines (2×5 MW) and a small solar array (around 20 MW) to reduce our town’s carbon emissions.

Previously, the local government hired a consultant (DNV) to assess the possibility of replacing part of the local distribution grid with hydrogen because there is a small part of the grid that needs to be replaced anyway. DNV concluded that right now (or as per the date of the study, 2018) hydrogen is way too expensive to substitute natural gas for heating; they made techno-economic calculations based on prices of €0,13 and €0,02 per kWh respectively for green hydrogen and natural gas.

Naturally, I was bummed when I read the report (which can be found here but it is only in Dutch) but the analysis makes sense: hydrogen right now is several times more expensive than natural gas. Nonetheless, I praise the initiative of my local government in taking the initiative to start the conversation about decarbonization pretty much by itself. This brings me to the topic of hydrogen valleys.

🔥 What about we co-host a webinar? Let's educate, captivate, and convert the hydrogen economy!

Hydrogen Central is the global go-to online magazine for the hydrogen economy, we can help you host impactful webinars that become a global reference on your topic and are an evergreen source of leads. Click here to request more details

What is a hydrogen valley?

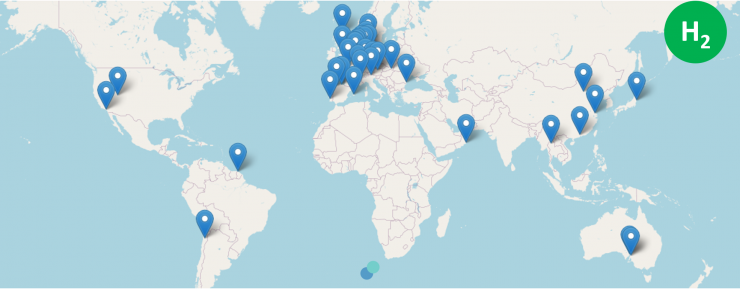

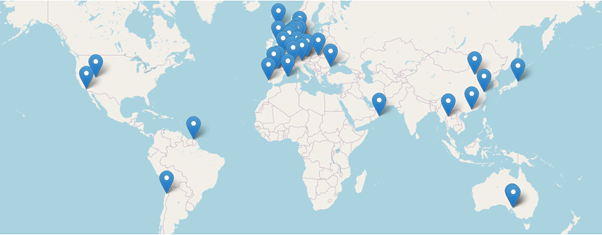

A hydrogen valley is essentially a project (usually funded by local, national and international funds) that clusters several industrial and research initiatives to carry out pilot projects across the complete hydrogen value chain (production, transport, distribution, and end use with storage sometimes in the mix). The website https://www.h2v.eu/, made by the FCH-JU (Fuel Cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking), the largest European public-private partnership that has supported and funded a significant part of the European hydrogen activities for more than a decade, has tracked all of the cluster projects that fulfill the criteria to be named hydrogen valley and compiled them in a handy map that you can see below:

Naturally, most hydrogen valleys that fulfill the European criteria are located in Europe. It is nonetheless enticing to see that the world is full of local entrepreneurs (both private companies and local municipalities) that gravitate around hydrogen and come together to advance the market introduction of hydrogen.

I have a kind of love/hate relationship with hydrogen valleys. On the one hand, I like that hydrogen activities are being promoted around the world; I feel personally engaged in the conversation when it is the local governments who take the initiative to decrease their own footprint and try to adopt new technologies. Also, I feel as if I am part of the conversation when the municipal government communicates directly with me, an important part of the community.

On the other hand, I feel that hydrogen valleys send the message that the national governments in Europe are shifting the burden of supporting hydrogen activities to the municipal governments. An allegory of the meeting between Jesus and Pontius Pilate comes to mind.

Some time ago I attended a webinar where HyDeal’s (a Pan-European lobby group that is heavily supporting hydrogen) spokesperson Thierry Lepercq expressed a similar opinion, saying that “50 years ago we were not talking about nuclear energy or natural gas valleys; the support came from the national governments”.

Hydrogen valleys are a nice initiative to involve municipal governments and members of the community in hydrogen projects. Nevertheless, they should be part of a larger plan proposed by the national governments to accelerate the introduction of hydrogen in Europe.

Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro.

The municipal governments have significantly less experience in developing roadmaps or accelerating market entry of any kind of technologies, not to mention that they are also bound by resources freed up by the national government and must adhere by the normativity imposed by national groups. Additionally, the municipal governments’ influence on the groups in charge of updating and creating new standards and policies is relatively small. Thus, municipal governments are not really in a position to effect significant change towards extrapolating the findings within the hydrogen valleys to create a new regulatory framework for hydrogen, for example (at least not beyond issuing a recommendation).

Another challenge that municipal governments face when taking part in hydrogen valleys is their (general) lack of technical expertise around hydrogen. From the meetings I have had with local representatives it appeared that, while their enthusiasm was clear, they recognized that they are not the competent authority to e.g., issue construction permits or allow the installation of hydrogen systems in their jurisdiction. As much engagement as can come from municipalities, their role is to be across the negotiating table, judging projects to assess the value to be brought to the community, not as part of the consortiums requesting subsidies.

The above being said, I do acknowledge the hydrogen valleys’ ability to spread awareness about hydrogen. Nevertheless, the widespread dissemination of the activities within the valleys is still left to international organizations such as the FCH-JU, thereby obfuscating most dissemination efforts done by local companies and governments.

All things considered, I believe that hydrogen valleys are an easy initiative by the national governments to help initiate the discussion about hydrogen while postponing their task to convert a high-level strategy into a detailed roadmap with concrete national milestones to broaden the adoption of hydrogen in the national economy. EC president Ursula von der Leyen famously supports hydrogen valleys, which means that hydrogen valleys are in the center of the European discussions. To me this feels like a way to postpone a clear and more succinct commitment that the EU must make. We all know that Europe is famously slow at adopting new trends and changing its viewpoint in general, so it does not surprise me that it would rather throw money at hydrogen instead of devising a comprehensive plan.

Do not get me wrong: I support hydrogen valleys. I think that hydrogen valleys belong in a broader plan that should be headed by the national governments, one where hydrogen valleys play a crucial role in spreading the adoption of hydrogen technologies without having to be the main (or in some cases, only) activities in a particular country. As a member of my local community, I welcome the opportunity to be part of the discussion, but I speak for my fellow residents when I say that we do not have the expertise nor the long-term vision to be a decision-making stakeholder within a hydrogen valley.

READ the latest news shaping the hydrogen market at Hydrogen Central

About the author

Dr. Julio C. Garcia-Navarro is a Hydrogen Project Coordinator at New Energy Coalition. He has worked in the hydrogen industry for nearly a decade, on topics such as hydrogen electrolysis, compression, and transportation. Besides hydrogen, he is passionate about Renewable Energy Systems and the Internet of Things.

Copyright © Hydrogen Central. All Rights Reserved.